The last Monday of January is National Bubble Wrap Day, a celebration of Alfred Fielding and Marc Chavannes’ invention that revolutionized product packaging, started Sealed Air Corporation, and provided us all with decades of soothing crackles. U.S. Pat. 3,142,599.

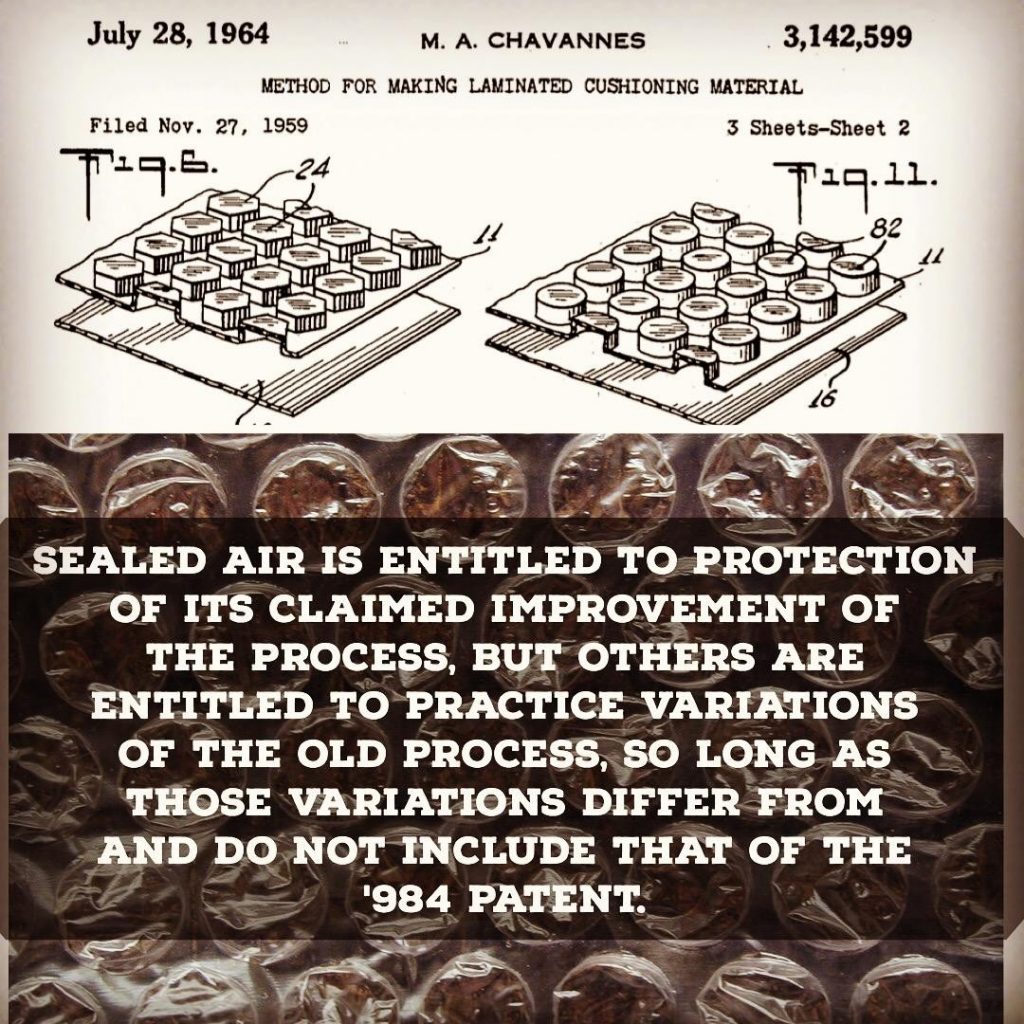

Initially intended as 3D wallpaper and later greenhouse insulation, the bubble wrap concept took off after Frederick Bowers’ 1960 suggestion to use it as a packaging material for IBM’s newest line of computer, the IBM 1401. When the first bubble wrap patent expired in 1981, Sealed Air tried to enforce its 1985-expiring process patent against cheap imports in the International Trade Commission. Although victorious in the ITC, the CCPA (Fed. Cir. predecessor) reversed on appeal, finding that one of the importers had successfully avoided infringement of Sealed Air’s patent under the doctrine of equivalents (DOE).

Sealed Air’s later Patent was specific to feeding two sheets that fused at a “kiss point” after the embossing roller. But the accused infringer applied melted plastic directly into the roller where it solidified before joining to the laminating sheet. Illustrating the difficulty of enforcing later expiring process patents, the court found the infringer was free to use variations of the expired process.