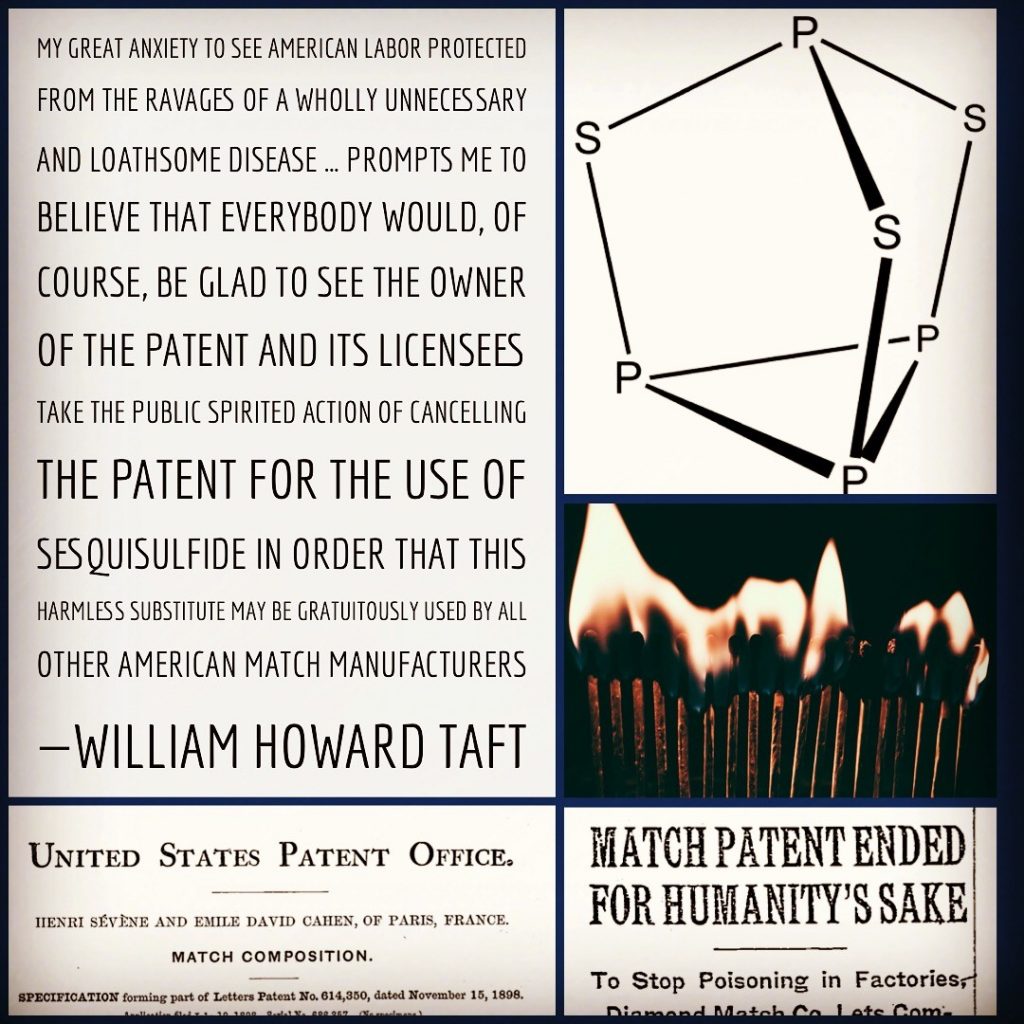

A box of matches used to contain enough white phosphorous to kill you. Deaths and suicides from eating match sticks were frequent, and workers in the industry developed phosphorous necrosis, or “phossy jaw,” a disease resulting in the deterioration of the teeth and jawbone.

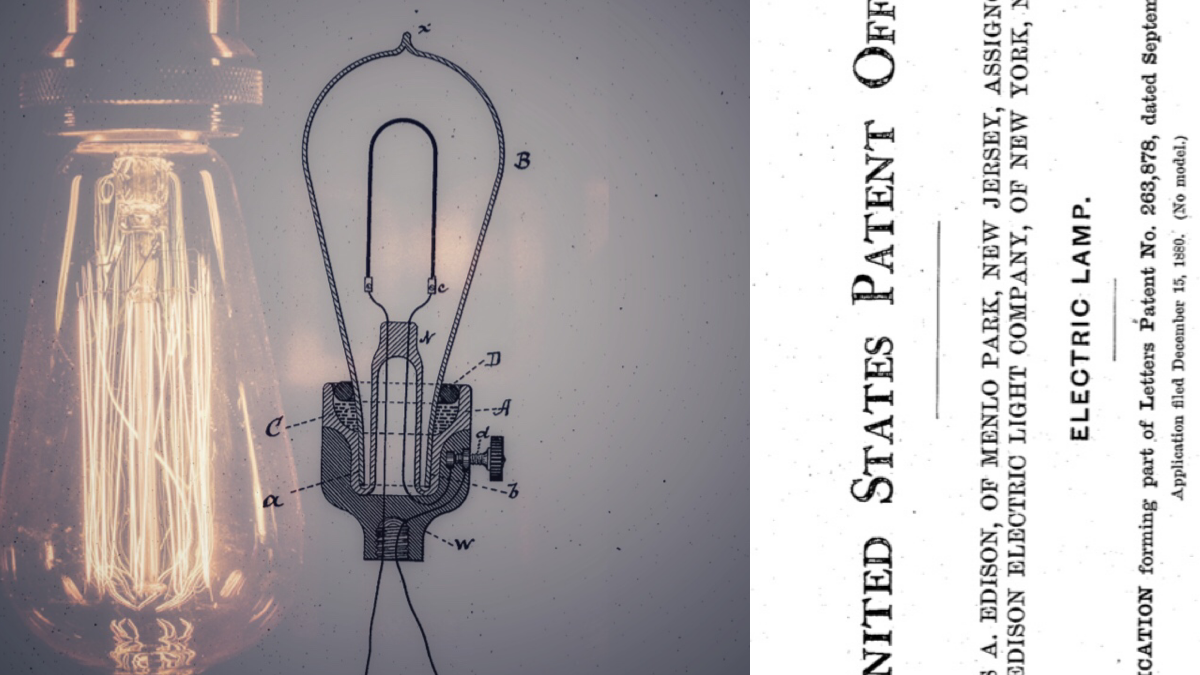

French chemists Henri Sévène and Emile Cahen patented their non-toxic phosphorous sesquisulfide for matchmaking as U.S. Pat. 614,350, and sold it to the Diamond Match Co for $100,000 in 1900.

Progressive opposition to the use of toxic white phosphorous in matchmaking led to a legislative effort to end it. Diamond supported the Federal legislation, hoping to avoid regulation on a state-by-state basis. It first offered its patent for license to the entire industry on favorable terms hoping it would encourage passage of the white phosphorous ban. Outside observers, however, viewed Diamond’s licensing terms as too tough and a public backlash ensued.

President Taft publicly called on Diamond to relinquish its patent. Fearing that it would lose the legislative effort, Diamond eventually disclaimed its entire patent and disclosed its own trade secret match composition to competitors.