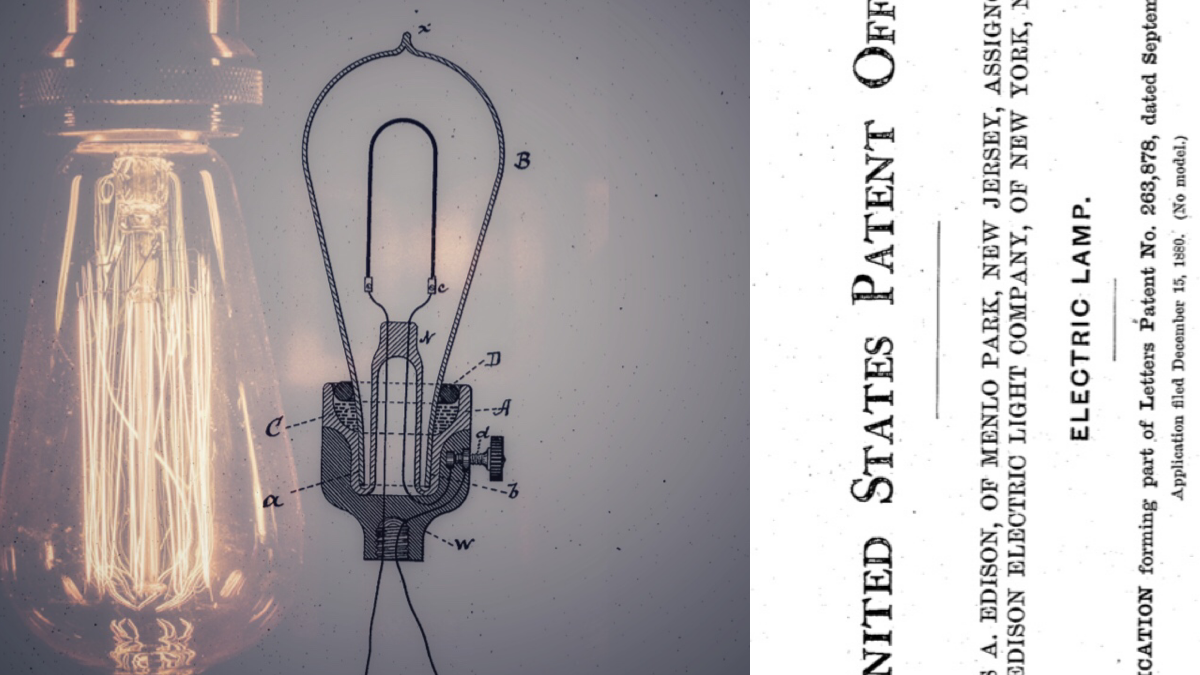

Thomas A. Edison, famed inventor of the first practical incandescent lamp, was granted U.S. Pat. 223,898 on January 27, 1880, which claimed “a filament of carbon of high resistance.”

Months after filing his application, Edison discovered a carbonized filament from bamboo in Japan could burn 1,200 hours. His patent was invalidated by the Patent Office based on an earlier patent to Sawyer, U.S. Pat. 205,144, but eventually upheld after six years of litigation.

Westinghouse sued Edison’s company, General Electric, under the Sawyer patent in a case that went to the Supreme Court, The Incandescent Lamp Patent, 159 U.S. 465 (1895).

The Court invalidated Sawyer’s patent noting that the materials described therein “were found to be so inferior to the bamboo, afterwards discovered by Edison, that the complainant was forced to abandon its patent in that particular, and take up with the material discovered by its rival.”

“I’ve not failed. I’ve just found ten thousand ways that don’t work”

Thomas A. Edison

Edison’s famous quote “I’ve not failed. I’ve just found ten thousand ways that don’t work” reflects his work in finding a material suitable for an incandescent bulb. Bamboo remained the material of choice until another GE inventor Irving Langmuir developed a practical way to make tungsten filament in 1913, U.S. Pat. 1,180,159.